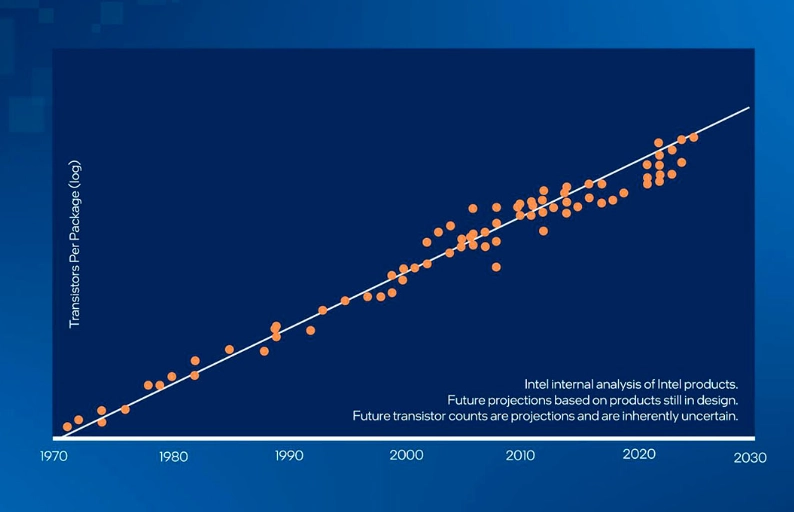

Let's get this out of the way first. If you're reading this to get a textbook definition of Moore's Law, you'll be disappointed. Gordon Moore's 1965 observation that transistor density doubles roughly every two years is just the starting line. The real story, the one that affects stock prices, startup valuations, and where you should put your investment dollars, happens after the physics gets hard. I've spent over a decade in tech finance, and I can tell you the biggest mistake investors make is treating Moore's Law as a simple tech trend. It's not. It's a financial and psychological force that has dictated the pace of global business for 50 years. And its changing rhythm is creating winners and losers most people haven't even identified yet.

The assumption of constant, cheap performance improvement became baked into every business plan. It allowed software to be bloated, it made "wait for the next generation" a viable product strategy, and it convinced investors that tech was a perpetual growth machine. That assumption is now cracking. The cost of advancing to the next chip node is astronomical. The CEO of a major semiconductor equipment firm, ASML, has spoken extensively about the complexity and cost of next-generation EUV lithography. This isn't just an engineering problem; it's an economic earthquake.

What You'll Discover in This Guide

What Exactly is Moore's Law (And What Everyone Gets Wrong)

Moore's original paper in Electronics Magazine was a forecast, not a law of nature. He was looking at cost. The magic wasn't just more transistors; it was more transistors per dollar. Performance went up, and the cost per unit of performance went down. That's the engine that drove the PC revolution, the internet, and smartphones.

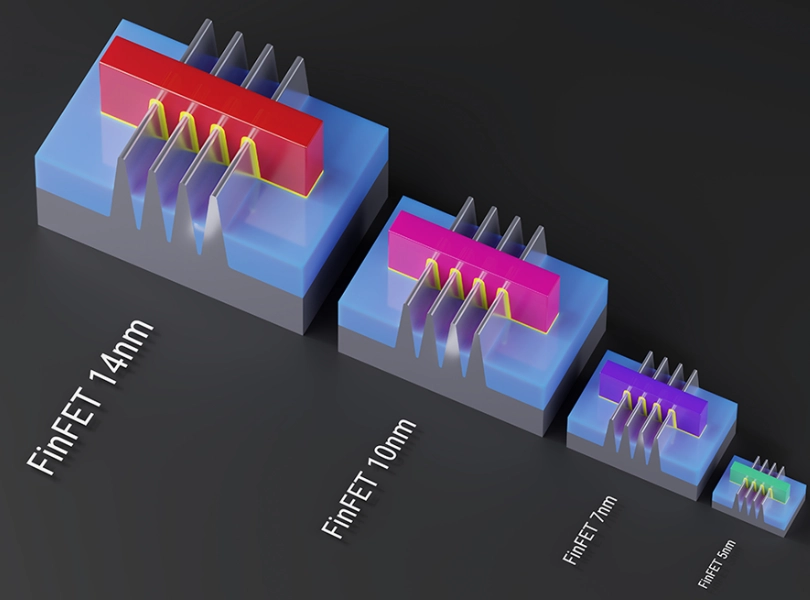

Here's the subtle error most analysts make: they focus solely on the "doubling" part for leading-edge chips (like your iPhone processor). They miss that the economic benefit of Moore's Law flows downstream. When a cutting-edge 3nm chip is new, the older 7nm or 14nm manufacturing lines don't disappear. They become cheaper to run. This "technology tail" is where the vast majority of chips are made—for cars, appliances, medical devices. The real economic value has been this cascading effect of cheaper, reliable technology for everyone.

That tail is now getting squeezed. The cost to build a new fab is so high that companies are reluctant to retire old ones, slowing the trickle-down of cheap capacity. This is why we have a "chip shortage" in mature nodes while leading-edge nodes face insane competition.

The Business Reality Behind the Curve

For decades, business strategy in tech could be lazy. Roadmaps were predictable. You could plan a product knowing that in 18 months, a chip twice as powerful would be available for the same price. That allowed for inefficiency.

The end of easy scaling forces a brutal rethink. It impacts three core areas:

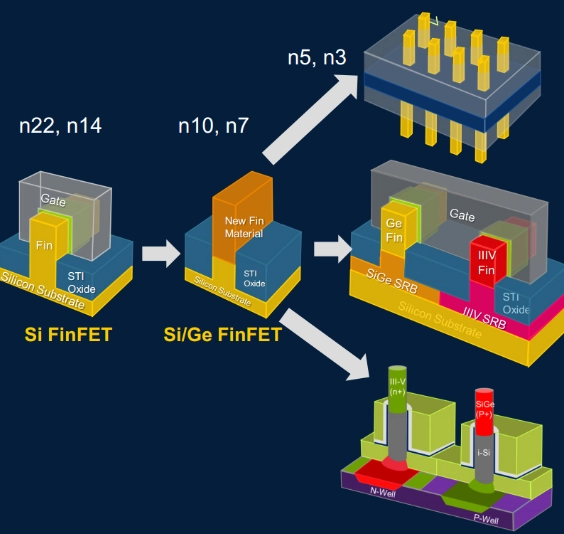

1. The R&D Pivot: From Scaling to Architecting

Companies can't just wait for TSMC or Samsung to deliver a smaller node. They have to design smarter. This means:

Specialization: Creating chips for specific tasks (Google's TPU for AI, Apple's M-series for laptops).

Advanced Packaging: Stacking chips vertically ("3D stacking") rather than just making them flat and smaller.

Software Co-Design: Writing software in tandem with hardware design, a discipline that was optional when hardware was always catching up.

This favors companies with deep, integrated engineering talent. The era of the pure software company riding on generic Intel hardware is fading.

2. The Capital Expenditure Cliff

The table below shows the problem in stark terms. It's not linear growth; it's exponential.

| Chip Manufacturing Node | Estimated Fab Cost (Billions USD) | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| 28nm (c. 2011) | $2 - $3 | Introduction of complex double patterning. |

| 7nm (c. 2018) | $7 - $10 | First use of Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) lithography. |

| 3nm (c. 2022) | $15 - $20 | Multiple EUV layers, atomic-scale precision. |

| Future (~2025+) | $25 - $30+ | New materials (e.g., Gate-All-Around transistors), quantum effects. |

At these prices, only a handful of companies on Earth can play the game. This leads to massive consolidation and strategic partnerships (like Intel's IFS foundry service trying to compete with TSMC). For investors, it means the semiconductor equipment and materials sector becomes as critical as the chip designers.

3. The Software Reckoning

This is the biggest sleeper effect. For years, developers prioritized speed of development over efficiency. Why spend a month optimizing code for a 10% gain when next year's processor would be 40% faster? That logic is broken. We're seeing a quiet renaissance in efficient programming languages (Rust, Go), leaner software, and a focus on algorithmic efficiency. Companies that master this will see their software run circles around competitors on the same hardware.

How Investment Strategy is Changing

The old playbook was simple: invest in the leading chip designer (Nvidia, AMD, Apple) and the leading manufacturer (TSMC). That's now table stakes, and it's crowded. The new opportunities are in the adjacencies.

Look upstream: The companies that make the tools to make the chips. Firms like ASML (EUV lithography monopoly), Applied Materials, and Lam Research. They are the picks and shovels in this gold rush, and their pricing power is immense.

Look sideways: At alternative computing architectures. The CPU-centric world of Intel is giving way to a heterogeneous mix. This boosts companies in:

- AI/ML Accelerators: (Nvidia, but also smaller players in specific niches).

- Data Center Efficiency: Companies that improve cooling, power delivery, and integration.

- Edge Computing: As sending all data to the cloud becomes a bottleneck, processing locally on efficient, specialized chips becomes key.

Look for integration, not just innovation: A company that can cleverly combine older, cheaper chips into a high-performance package through smart software and interconnect technology might deliver better returns than one burning cash on the bleeding edge.

Industry Impact: Who Wins, Who Loses

Let's get concrete. This isn't just about tech stocks.

Potential Winners:

Automotive & Industrial: These sectors use mature-node chips (28nm-90nm). If the leading-edge scramble keeps semiconductor R&D focus there, these reliable, cheaper nodes could see longer, more stable supply and innovation in robustness, not just speed.

Software Optimization Firms: Tools for profiling code, finding inefficiencies, and auto-optimizing for specific hardware will be in high demand.

Materials Science Companies: The next breakthroughs may come from new materials (graphene, new semiconductors), not just shrinking silicon.

Potential Losers (or Challenged):

Consumer Tech Companies with Thin Margins: If the cost of performance gains rises, they can't easily pass it to consumers. Their upgrade cycles may lengthen, hurting revenue.

Businesses Built on "Free" Compute: Some SaaS and cloud models assumed underlying compute costs would perpetually fall. That cost curve is flattening, squeezing margins.

Generic Hardware Manufacturers: Companies selling undifferentiated boxes powered by generic chips will face intense cost pressure.

Your Next Move: A Practical Framework

So what do you, as an investor or business-minded person, do with this?

First, audit your exposure. Look at your portfolio or business. How reliant is it on the assumption of perpetually cheaper, faster general-purpose compute? If it's central, you have a latent risk.

Second, rebalance for the shift. Consider allocating a portion of tech investments away from pure-play consumer chip designers and toward the enablers (semiconductor capital equipment), the innovators in new architectures (AI chips, quantum computing startups), and the efficiency experts (software optimization, advanced cooling).

Finally, think in systems, not components. The highest value will accrue to companies that control the integrated stack—chip design, software, and services—like Apple does. Vertical integration and co-design are becoming competitive moats.

Moore's Law isn't dead. It's evolving from a physical mandate into a business philosophy. The goal is no longer just density; it's efficiency, specialization, and system-level wisdom. The investors and companies that understand this nuance won't just survive the transition—they'll define the next era.