You're looking at two investment proposals. One promises a 25% return, the other 18%. The choice seems obvious, right? Maybe not. That 25% figure is the Internal Rate of Return, or IRR, and in my years of analyzing projects, I've seen more bad decisions made by blindly chasing a high IRR than almost any other single metric. It's a powerful tool, but it's not a simple scorecard. Think of it less like a grade and more like the engine diagnostic code for your investment—it tells you something is happening, but you need to pop the hood to understand why.

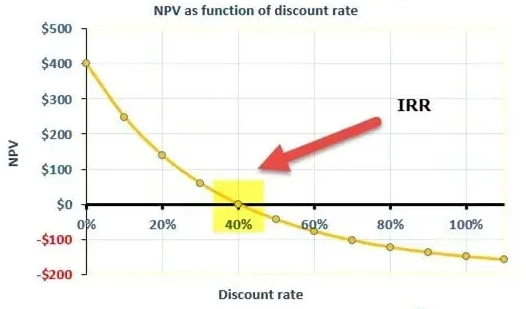

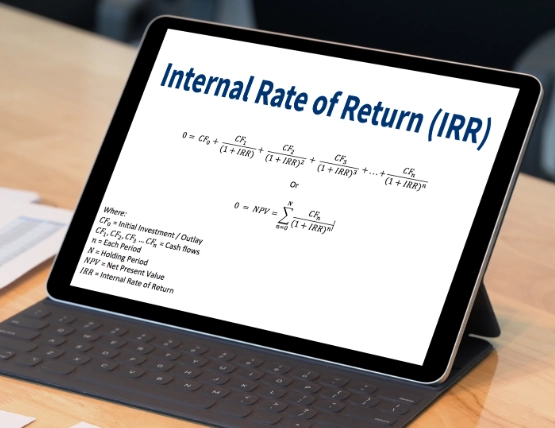

IRR cuts through the noise of absolute dollar amounts. It gives you a percentage, an annualized rate of growth that your investment is expected to generate. It's the rate that makes the net present value (NPV) of all cash flows from a project equal to zero. In plain English, it's the break-even interest rate for your project. If your project's IRR is higher than your required rate of return (your "hurdle rate"), it's theoretically a green light.

But here's where people get tripped up. They treat IRR as the final answer. They don't ask what's behind that shiny percentage. This guide is about getting under the hood.

What You'll Learn in This Guide

What IRR Really Means (And What It Doesn't)

Let's strip away the finance jargon. Imagine you lend a friend $1,000. They pay you back $100 at the end of each year for three years, and then a final $1,100 in year four. The IRR of this "loan" is 10%. It's the consistent annual return you're earning on your money, considering the timing of each payment.

That's the core idea. The IRR is the project's implied compound annual growth rate. The Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) Institute curriculum emphasizes that IRR is the discount rate that forces NPV to zero, which is a precise but dry definition. The real-world meaning is about growth and efficiency.

But the first non-consensus point I'll make is this: IRR is obsessed with timing, sometimes to a fault. It inherently values a dollar received tomorrow more than a dollar received in five years, which is correct in principle (time value of money). However, this sensitivity can distort comparisons between projects with different cash flow patterns. A project that gives you a big, early payoff will often sport a higher IRR than a slower-burning, longer-term project—even if the latter creates more total wealth.

How to Calculate IRR: A Step-by-Step Walkthrough

You don't need to be a math whiz. In the real world, everyone uses Excel, Google Sheets, or a financial calculator. The formula is iterative—computers guess and check until they find the rate that works. Your job isn't to do the calculation manually; it's to set up the cash flows correctly. This is where most errors happen.

Let's work through a concrete example. You're considering buying into a small, local café.

Case Study: The "Urban Grind" Café Investment

Scenario: You're asked to invest $80,000 upfront for a 25% stake. The business plan forecasts the following net cash flows to you over 5 years, after all expenses and reinvestments. Year 5 includes the sale of your stake back to the other owners.

Here’s the cash flow schedule:

| Period | Cash Flow Description | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Year 0 (Today) | Initial Investment (Outflow) | -$80,000 |

| Year 1 | Your share of profit | $5,000 |

| Year 2 | Your share of profit | $12,000 |

| Year 3 | Your share of profit | $18,000 |

| Year 4 | Your share of profit | $22,000 |

| Year 5 | Profit + Sale of Stake | $110,000 |

In Excel, you'd list these in a column: -80000, 5000, 12000, 18000, 22000, 110000. Then use the formula =IRR(A1:A6). Excel will return approximately 14.3%.

That's the IRR. It means the projected annualized return on your $80k, given that specific timing of cash inflows, is 14.3%. If your personal hurdle rate (maybe the return you could get from a stock index fund) is 10%, this project clears the bar.

The Manual Check: Understanding NPV at the IRR

To really see what's happening, calculate the NPV using the IRR as the discount rate. Discount each future cash back to today's value using the formula CF / (1 + r)^n, where r=14.3%. Add them all up, including the initial -$80,000. The sum will be zero (or very close, due to rounding). This proves the IRR is the rate that makes you indifferent, in present value terms, between investing and not investing.

The Hidden Traps and Limitations of IRR

This is the part most articles gloss over. They present IRR as a flawless king. It's not. Here are the traps that can turn that attractive percentage into a terrible decision.

1. The Reinvestment Assumption Fairy Tale: IRR implicitly assumes that all intermediate cash flows (like those yearly café profits) can be reinvested at that same high IRR. Think about that. Our café has a 14.3% IRR. The metric assumes you can take the $5,000 profit from Year 1 and reinvest it somewhere else at 14.3% for the next four years. That's almost certainly unrealistic. In reality, you might park it in a savings account at 4%. This flaw overstates the true potential of projects with high IRRs and early cash flows.

2. The "Multiple IRR" Problem: If your cash flows change direction more than once (e.g., invest, get income, reinvest more, then get final payoff), the math can produce two or more valid IRRs. Which one is right? Neither. The metric breaks down. This happens in projects like mining or phased real estate development where large environmental cleanup costs (outflows) come long after the initial income.

3. Scale Blindness (The Most Dangerous One): I mentioned it earlier but it's worth a story. Early in my career, our team was pumped about a tech plugin project showing a 70% IRR. We almost fast-tracked it until someone asked for the NPV. It was positive but tiny—about $15,000. We were about to tie up managerial resources for a $15k gain while ignoring larger projects with 18% IRRs that were creating millions in value. IRR didn't show that. NPV shows magnitude, IRR shows efficiency. You need both.

4. It Can't Compare Projects of Different Lengths Effectively: A 30% IRR over 2 years is not directly comparable to a 25% IRR over 10 years. The time horizons are different. Would you rather double your money in 2 years (~41% annual IRR) or triple it in 10 years (~12% annual IRR)? IRR alone doesn't answer that; it depends on your goals and what you can do with the money when you get it back.

Using IRR in Real Investment Decisions: A Practical Framework

So how should you actually use IRR? Not as a standalone go/no-go signal. Use it as one input in a broader framework.

Step 1: Calculate Both IRR and NPV. Always. Use a discount rate that reflects your cost of capital or minimum acceptable return. If the NPV is significantly positive at that rate, the project adds value. The IRR tells you your margin of safety—how much higher the project's return is compared to your hurdle rate.

Step 2: For Mutually Exclusive Projects, Lead with NPV. If you can only choose one project (e.g., build Factory A or Factory B on the same land), the project with the higher NPV adds more absolute wealth, even if its IRR is lower. Harvard Business Review's historical case studies on capital budgeting are full of examples where companies chose the lower-NPV, higher-IRR project and regretted it.

Step 3: Use Modified IRR (MIRR) for Sanity. MIRR is a variant that fixes the unrealistic reinvestment assumption. You specify a conservative "finance rate" (for negative flows) and a "reinvestment rate" (for positive flows)—like your savings account or average market return. The result is a more sober, realistic annual return figure. In our café example, if we assume reinvestment at 6%, the MIRR might drop to 12.5%. That's a more defensible number.

Step 4: Layer in Qualitative Factors. IRR is purely quantitative. What about strategic fit? Risk profile (a stable utility's 8% IRR is different from a biotech startup's 30% IRR)? Environmental or social impact? These never show up in the calculation but must be in the final decision.

Think of your analysis like this: NPV tells youhow much richer you'll get. IRR tells you how efficient the project is at making you richer. MIRR gives you a realistic efficiency estimate. And your judgment ties it all together.

Your Top IRR Questions Answered

Internal Rate of Return is a lens, not a crystal ball. It transforms a messy stream of future cash into a single, comparable percentage. That's its power. Its weakness is that it simplifies too much, hiding assumptions about reinvestment and scale. Use it as the sophisticated tool it is—with awareness of its flaws, in partnership with NPV, and tempered by your own judgment about what an investment truly means for your goals. Don't just chase the highest percentage. Seek the combination of efficiency, scale, and strategic sense that builds real, durable wealth.