You're looking at a company, maybe thinking of investing, or perhaps even acquiring it. The first number everyone sees is the share price. The second is the market capitalization. It's tempting to think that's the price tag. Let me stop you right there. It's not.

If you're serious about valuation—truly understanding what a business is worth in a takeover or a comparative analysis—you need to look at Enterprise Value (EV). Market cap tells you what the equity is worth. Enterprise Value tells you what the entire operating business is worth to all capital providers. It's the number that pops up on the first page of any serious M&A model or leveraged buyout analysis. Getting it wrong means you could massively overpay or miss a hidden gem.

What You'll Learn

The Core Concept: Why EV is the "Takeover Price"

Imagine you want to buy a house. The seller is asking $500,000. But there's a $300,000 mortgage on it. And in the basement safe, the seller has left $50,000 in cash.

What's the real cost to you, the buyer? You'd pay $500k for the equity, assume the $300k debt, and get to keep the $50k cash. Your net outlay? $500k + $300k - $50k = $750k. That $750k is the Enterprise Value of the house—the total economic value transferred.

Enterprise Value works the same way for a company.

This is why it's superior to market cap for comparisons. A tech startup with $2 billion in market cap and $1.5 billion in cash is a very different beast from a manufacturing firm with the same market cap but $1.5 billion in debt. Their equity values are identical, but their enterprise values are worlds apart.

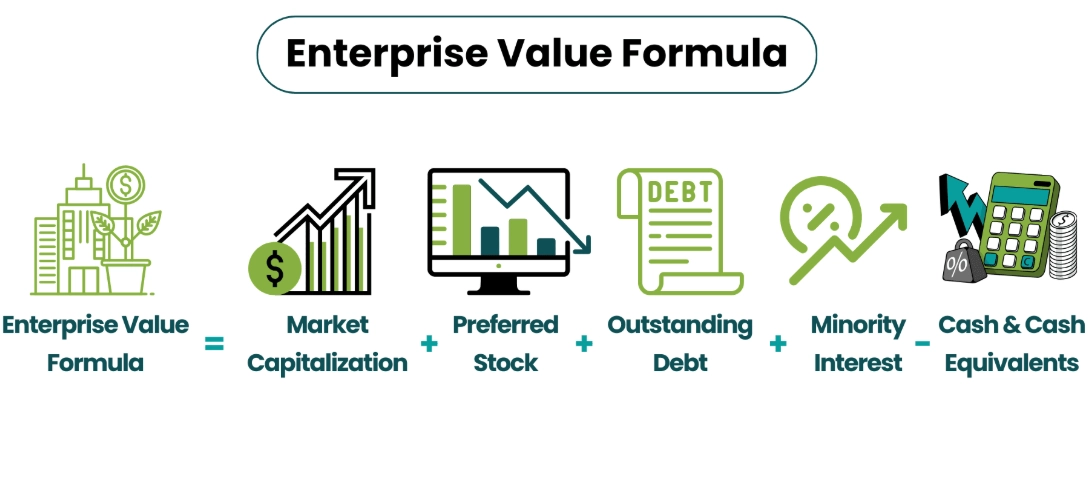

Breaking Down the Enterprise Value Formula

Let's unpack this, piece by piece. It's not just an equation to memorize; you need to know what each component really means and where to find it.

1. Market Capitalization (The Equity Sticker Price)

This is the starting point. Market Cap = Current Share Price × Total Diluted Shares Outstanding. Don't just use the basic shares. You need the fully diluted count, which includes in-the-money stock options, warrants, and convertible securities. If you ignore these, you're undervaluing the equity claim. Check the company's latest 10-K or 10-Q filing (like from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission's EDGAR database) for the diluted share count.

2. Total Debt (The Liability You Assume)

This includes all interest-bearing liabilities: short-term debt, current portion of long-term debt, and long-term debt. You find these on the balance sheet. Here's a nuance most gloss over: you should technically use the market value of debt, not the book value. Debt on the balance sheet is at historical cost. If interest rates have risen, that old, low-coupon debt is worth less in the market. For a precise valuation, you'd discount the future debt payments at the current market rate. In practice, for a quick analysis, book value is a common proxy, but know it's an approximation.

3. Minority Interest & Preferred Shares (Other Capital Claims)

Minority Interest (Non-controlling Interest): This appears when a company consolidates a subsidiary it owns 51%-99% of. The portion it doesn't own (the 1%-49%) is a claim on that subsidiary's assets. If you're buying the entire parent company, you're effectively buying 100% of that sub, so you need to add this value.

Preferred Shares: These are hybrid securities, often with fixed dividends, that sit above common equity in the capital structure. They are another claim on the firm's value and must be added. You'll find both items on the balance sheet under equity, but they are not part of common equity.

4. Cash & Cash Equivalents (The Asset You Get)

This is subtracted because as the new owner, this cash is yours to use immediately—you could theoretically use it to pay down part of the debt you just assumed. It includes literal cash, bank deposits, and highly liquid investments with maturities under 90 days (like Treasury bills). Warning: Be careful with "cash equivalents." Some companies park cash in long-term investments or restricted accounts. If it's not truly liquid and accessible for operations or debt repayment, you might consider excluding it from the subtraction. Always read the footnotes.

Step-by-Step Calculation: The TechNovate Inc. Example

Let's make this concrete. Say we're analyzing a fictional mid-cap tech firm, TechNovate Inc. (Ticker: TNVT). Here's the data we've pulled from its latest financial statements and market feed:

| Data Point | Value (in millions) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Current Share Price | $45.50 | Market Data |

| Diluted Shares Outstanding | 110.0 | Latest 10-Q, Note 12 |

| Short-Term Debt | $75.0 | Balance Sheet |

| Long-Term Debt | $325.0 | Balance Sheet |

| Cash & Cash Equivalents | $220.0 | Balance Sheet |

| Marketable Securities (>90 days) | $50.0 | Balance Sheet / Footnotes |

| Minority Interest | $0.0 | Balance Sheet (none present) |

| Preferred Stock (Liquidation Value) | $40.0 | Balance Sheet, Equity section |

Now, let's walk through the math.

Step 1: Calculate Market Cap.

$45.50/share × 110.0 million shares = $5,005.0 million.

Step 2: Identify Total Debt.

Short-Term Debt ($75.0) + Long-Term Debt ($325.0) = $400.0 million.

Step 3: Identify Other Claims.

Minority Interest = $0.0. Preferred Stock = $40.0 million.

Step 4: Identify Deductible Cash.

Here's a judgment call. The pure "Cash & Equivalents" is $220.0M. Those "Marketable Securities" with maturities over 90 days are less liquid. For a conservative EV calculation focused on highly accessible assets, we'll only subtract the $220.0M. In a more aggressive take, you might include part of the $50.0M. I'll stick with the standard definition: $220.0 million.

Step 5: Plug it all into the EV Formula.

EV = Market Cap + Debt + Preferred Stock - Cash

EV = $5,005.0 + $400.0 + $40.0 - $220.0

EV = $5,225.0 million, or $5.225 billion.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

I've seen these errors derail analyses time and again.

Mistake 1: Using Basic Shares Instead of Diluted Shares. This understates equity value, especially for companies with large employee option pools. Always use the diluted count.

Mistake 2: Forgetting Minority Interest or Preferred Stock. This is a pure error that inflates the value of common equity by ignoring other legitimate claims. It's like pricing a house but forgetting there's a separate garage apartment with a tenant who has rights.

Mistake 3: Misunderstanding "Cash." Subtracting restricted cash or including long-term investments as cash equivalents artificially lowers EV, making the company look cheaper than it is. Read the financial statement notes on cash.

Mistake 4: The "Negative EV" Trap. Sometimes, a company's cash pile exceeds the sum of its market cap and debt, leading to a negative Enterprise Value. This seems like a free lunch—buy the company for less than its net cash! But it's often a sign the market believes the business is burning cash rapidly or has huge impending liabilities. Tread very carefully.

How to Use EV in the Real World: Valuation Multiples

Calculating EV is just step one. Its real power is as the numerator in valuation multiples, which allow for clean comparisons across companies with different capital structures.

The king of these multiples is EV/EBITDA (Enterprise Value to Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization).

Why? Because EV represents the value of the business to all capital providers, and EBITDA represents the core operating cash flow available to all those providers (before financing costs, taxes, and non-cash charges). They match in scope.

Let's go back to TechNovate. Suppose its last twelve months (LTM) EBITDA is $435 million.

EV/EBITDA = $5,225 million / $435 million = 12.0x.

Now you can compare this 12.0x multiple to:

- TechNovate's own historical average (was it 10x last year? Why the expansion?).

- Direct competitors. If rival firms trade at 14x EBITDA, TechNovate might look relatively cheap.

- Precedent M&A transactions. If similar tech companies were acquired at 15x EBITDA, TechNovate could be an attractive target.

Other useful EV-based multiples include EV/Revenue (for high-growth, unprofitable companies) and EV/EBIT (when you want to consider depreciation differences).

The moment you start thinking in these terms—comparing the total business value to its operating earnings—you've moved beyond the amateur investor looking at just the P/E ratio. You're analyzing like a banker or a private equity firm.