Let's cut to the chase. If you're running a business that sells physical products, there's one number on your financial statements that deserves more of your attention than any other. It's not your revenue. It's not your net profit. It's your Cost of Goods Sold (COGS). Get this wrong, and you could be pricing yourself into oblivion or celebrating profits that don't actually exist. I've seen it happen too many times. A bakery owner wonders why she's so busy but broke, a retailer can't figure out why his "great margins" aren't translating to cash in the bank. Nine times out of ten, the root of the mystery is a misunderstood or miscalculated cost of goods sold.

This isn't just accounting jargon. This is the real, direct cost of putting the product you sold into your customer's hands. Understanding it is the difference between guessing and knowing.

What You'll Learn in This Guide

What Exactly Is Cost of Goods Sold?

Think of COGS as the price tag of your sold inventory. It's the total direct costs attributable to the production or purchase of the goods that left your shelf or warehouse during a specific period. The keyword here is direct.

If you make wooden tables, the wood, screws, stain, and the wages of the carpenter building them are in COGS. The salary of the manager who oversees the carpenter? That's an operating expense. If you're a retailer, it's the wholesale price you paid your supplier for the jeans you sold. The rent for your storefront? Operating expense.

The Core Principle: A cost is only part of COGS if it would not exist if you didn't produce or acquire that specific unit. No sale, no cost.

This distinction is crucial for calculating your gross profit (Revenue - COGS), which tells you the fundamental profitability of your core product before overheads eat into it. A healthy gross profit margin is your business's first line of defense.

The COGS Formula, Demystified

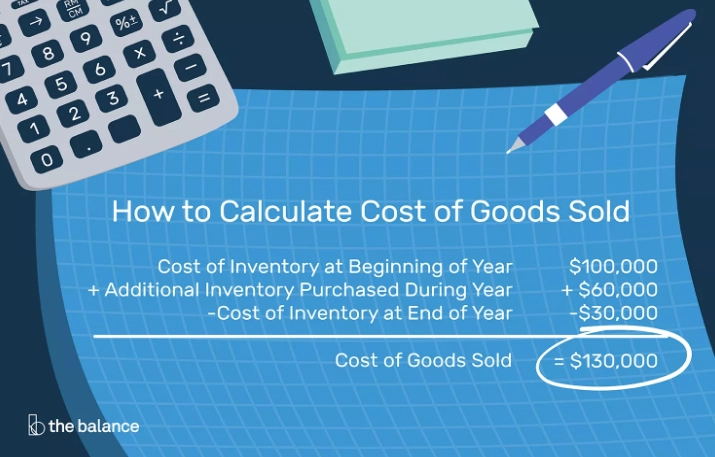

The standard cost of goods sold formula looks simple: Beginning Inventory + Purchases During the Period - Ending Inventory = COGS.

But each component has traps. Let's use a real-world scenario.

A Case Study: "Brewed Awakening" Coffee Roastery

Sarah runs "Brewed Awakening." On January 1st, her warehouse had $5,000 worth of green coffee beans (Beginning Inventory). In January, she bought another $15,000 worth of beans from her suppliers (Purchases). On January 31st, she counted what was left—beans worth $4,000 (Ending Inventory).

Her COGS calculation for January seems straightforward:

$5,000 (Beginning) + $15,000 (Purchases) - $4,000 (Ending) = $16,000.

That $16,000 represents the direct cost of the beans she roasted and sold in January. But here's where most small business owners stop, and that's a mistake. This $16,000 is only the cost of the raw material. For a manufacturer like Sarah, her true COGS must also include the direct labor of her roaster and the manufacturing overhead directly tied to production.

Let's say in January:

- Her roaster's wages for hours spent roasting: $3,000

- Factory utilities (gas for roaster, electricity for grinding/packaging machines): $800

- Depreciation on the roasting machine for January: $200

Her complete COGS calculation is:

$16,000 (Direct Materials) + $3,000 (Direct Labor) + $1,000 (Manufacturing Overhead) = $20,000.

See the difference? If she only used the $16,000 figure, she'd be overstating her gross profit by $4,000. That's a dangerous illusion.

The 3 Most Common (and Costly) COGS Mistakes

After consulting with dozens of businesses, I see these errors on repeat.

1. Treating All Purchases as Immediate COGS. This is the retailer's classic error. You buy 100 shirts in March for $1,000 and sell 70 of them by month's end. The temptation is to book the entire $1,000 as March's COGS. Wrong. Only the cost of the 70 shirts sold ($700) belongs in March COGS. The $300 for the remaining 30 shirts stays in your inventory asset account until you sell them. Failing to do this makes your profitability look wildly different from month to month.

2. Ignoring "Hidden" Direct Costs. Like Sarah almost did. For a service business with a product component (e.g., a caterer), the cost of the chef's time preparing the food is a direct labor cost that belongs in COGS. For an e-commerce store, the cost of shipping the product to the customer is a fierce debate. The IRS allows it as part of COGS, and I strongly recommend including it there. Why? Because it gives you a truer picture of your product's landed cost to the customer.

3. Inconsistent Inventory Tracking. Are you using FIFO (First-In, First-Out), LIFO (Last-In, First-Out), or Average Cost? The method you choose changes your COGS number, especially in times of inflation. Pick one, document it, and stick with it consistently. Switching methods is a red flag and a logistical nightmare. For most small businesses, Average Cost is the simplest and most logical.

Pro Tip You Won't Hear Often: Many guides tell you to include "freight-in" (shipping costs from your supplier to you) in COGS, which is correct. But they rarely mention what to do with discounts. If you get a 2% early payment discount from your supplier, you should reduce the cost of your purchase, and therefore your COGS, by that 2%. Capturing these small adjustments systematically is a hallmark of sharp financial management.

COGS vs. Operating Expenses: Why Mixing Them Up Hurts

Confusing COGS with operating expenses (OpEx) distorts your key financial metrics. It's like using a map with the wrong scale—you'll make poor navigation decisions.

| Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) | Operating Expenses (OpEx) |

|---|---|

| Directly tied to production/sale of specific goods. Varies directly with sales volume. | Indirect, necessary to run the business. Often fixed or semi-variable. |

| Examples: Raw materials, direct labor (wages of production workers), factory utilities, packaging, freight-in, depreciation on production equipment. | Examples: Rent, admin salaries, marketing/advertising, office supplies, professional fees, insurance, depreciation on office computers. |

| Appears on the Income Statement and is subtracted from Revenue to calculate Gross Profit. | Appears on the Income Statement and is subtracted from Gross Profit to calculate Operating Income. |

| Impact: A high or rising COGS lowers your Gross Profit Margin. This points to production or procurement inefficiencies. | Impact: High OpEx lowers your Operating Margin. This points to administrative or sales inefficiencies. |

Why does this matter for decision-making? If your gross profit margin is shrinking, you look at COGS: renegotiate with suppliers, improve production efficiency. If your operating margin is shrinking but gross profit is stable, you look at OpEx: is marketing spending effective? Is office rent too high?

Actionable Strategies to Optimize Your COGS

Lowering your COGS isn't about buying cheaper, inferior materials. It's about increasing efficiency and reducing waste.

- Negotiate, Don't Just Accept: Build relationships with suppliers. Ask for bulk discounts, better payment terms, or price matches. Can you commit to a quarterly volume for a 5% discount?

- Conduct a "Waste Audit": In manufacturing, measure your scrap. In food service, track spoilage. In retail, analyze shrink (theft, damage). A 2% reduction in material waste flows straight to your bottom line.

- Review Your Product Mix: Use your COGS data to identify your most and least profitable items. Are you spending disproportionate effort on low-margin products? Consider repricing, redesigning, or discontinuing them.

- Technology for Tracking: Move beyond spreadsheets. A basic inventory management system can automate tracking, give you real-time COGS insights, and prevent stockouts or overstocking, which ties up cash.

I worked with a client who made custom furniture. He was frustrated with low profits. When we dug into his cost of goods sold calculation, we found he wasn't allocating the full time his lead carpenter spent on complex designs. He was only counting material costs. Once we properly accounted for that direct labor, the true cost of his premium pieces became clear, allowing him to price them correctly. His sales volume dipped slightly, but his profitability soared.

Your Burning COGS Questions Answered

Is shipping to the customer part of COGS or an operating expense?

The IRS gives you a choice, but for managerial clarity, I always recommend including it in COGS. Think about it: if you sell a heavy item, the shipping cost is a direct, variable cost of fulfilling that specific sale. Including it in COGS gives you the true "landed cost" of the product for that customer. If you bury it in operating expenses, you lose visibility into how shipping impacts the profitability of different products or sales channels.

How do I calculate COGS for a service business?

Pure service businesses (consultants, lawyers) don't have COGS. But if your service has a tangible product component, you do. A graphic designer selling logo files has no COGS. But that same designer selling printed brochures has COGS: the cost of paper, ink, and printing labor. A cleaning service using its own supplies has COGS for those supplies. The rule still applies: if the cost is directly tied to delivering the specific service product, track it separately.

Can I lower my COGS without sacrificing quality?

Absolutely, and this should be the primary goal. Focus on efficiency, not cheapness. Renegotiate supplier contracts based on loyalty and volume, not by demanding lower-grade materials. Reduce waste in your production process. Streamline packaging to use less material without compromising protection. Sometimes, buying in slightly larger quantities with a reliable supplier gets you a better unit price without quality loss. The goal is to get the same or better output for less input cost.

My accountant uses a different COGS number for taxes than I use for management. Is that normal?

Unfortunately, it can be. For tax purposes, especially with complex inventory, accountants may use standardized methods or make conservative estimates that simplify their work. For running your business, you need granular, accurate data. Have a conversation with your accountant. Explain you need a management COGS figure that reflects reality so you can make pricing and operational decisions. A good accountant will help you bridge this gap, perhaps by maintaining a separate managerial accounting schedule.

How often should I be calculating my COGS?

At a minimum, monthly, aligned with your financial statements. If you have high-volume, low-margin products (like a grocery store), you might benefit from weekly or even daily tracking of key items. In today's world, with cloud-based POS and inventory systems, there's little excuse for not having near-real-time visibility. You can't manage what you don't measure.