Let's cut to the chase. If you're running a business that sells anything—widgets, software subscriptions, artisanal coffee—there's one number that matters more than almost any other for your day-to-day survival. It's not your revenue. It's your Cost of Goods Sold, or COGS. Get this wrong, and you're basically guessing at your profitability. I've seen too many smart entrepreneurs with great products watch their margins evaporate because they misunderstood or mismanaged their COGS.

It's the direct cost of creating the product you sell. Think of it as the financial pulse of your production line.

What You'll Find Inside

What COGS Really Means (Beyond the Textbook)

Yes, the textbook definition is "the direct costs attributable to the production of the goods sold by a company." But that's sterile. In practice, COGS is the story of your product's journey from raw stuff to finished item, told in dollars and cents.

For a bakery, it's the flour, eggs, butter, and the baker's wages for the hours spent mixing and baking. For a SaaS company, it might be the server costs and the salaries of the customer support team. The key word is direct. If you can't tie a cost directly and exclusively to a unit of product, it probably doesn't belong in COGS.

Calculating COGS: The Formula and The Common Screw-ups

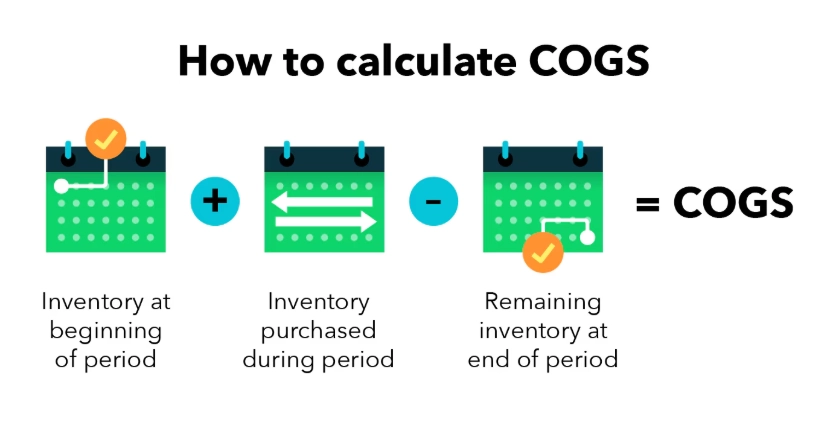

The basic COGS formula is simple:

COGS = Beginning Inventory + Purchases During the Period – Ending Inventory

Let's make it concrete. Imagine you run a small furniture business, "Oak & Craft."

- On January 1st, you have $20,000 worth of wood, hardware, and half-finished tables (Beginning Inventory).

- In January, you buy another $15,000 of oak planks and steel legs (Purchases).

- On January 31st, you count everything left. You have $10,000 worth of materials and unfinished products (Ending Inventory).

Your COGS for January is: $20,000 + $15,000 - $10,000 = $25,000. That's the direct cost of the materials that went into the tables you finished and sold (or are ready to sell) that month.

But that's just materials. A complete COGS calculation for a manufacturer includes three pillars:

| Pillar | What It Includes | Oak & Craft Example |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Materials | Raw materials and components that become part of the product. | Oak wood, steel table legs, wood glue, stain. |

| Direct Labor | Wages for employees directly involved in production. | Hourly wages for the carpenter building the tables. |

| Manufacturing Overhead | Indirect costs of the production facility only. | Depreciation on saws/sanders, factory utilities, salary of the production floor supervisor. |

The "Manufacturing Overhead" is the trickiest. It's still part of COGS, but it's allocated, not direct. If your factory's electricity bill is $1,000 and you make 100 tables, you might allocate $10 of electricity to each table's COGS. This requires a bit more accounting rigor.

How COGS Dictates Your Gross Margin

This is the magic. COGS is the primary driver of your Gross Profit and Gross Margin.

Gross Profit = Revenue – COGS

Gross Margin = (Gross Profit / Revenue) x 100

Let's say Oak & Craft sells a dining table for $1,200. If the COGS for that table (materials, labor, allocated overhead) is $700, then:

Gross Profit = $1,200 - $700 = $500

Gross Margin = ($500 / $1,200) x 100 = 41.7%

That 41.7% is your first and most important measure of business health. It tells you how efficiently you're turning raw materials into profit, before you pay for marketing, rent, or your own salary. Investors, like those reading analyses on Investopedia, scrutinize this number. A declining gross margin is a huge red flag—it means your production is getting less efficient or your costs are rising faster than your prices.

I once consulted for a craft brewery whose gross margin was slipping. They were focused on marketing to sell more beer. When we dug in, we found their COGS had crept up because of inefficient water usage and hops waste during the brewing process. Fixing those production issues did more for their bottom line than any ad campaign.

Actionable Strategies to Lower Your COGS

You can't just wish for a lower COGS. You have to engineer it. Here are levers you can actually pull, moving from easiest to most strategic.

1. Supplier & Inventory Management

This is low-hanging fruit. Don't just accept the first price from your supplier. Get quotes from three. Ask about bulk discounts for larger, less frequent orders. But be careful—bulk buying ties up cash and risks obsolescence. Use inventory management software to find the sweet spot. The goal is to reduce the cost per unit of your materials without hurting quality or creating storage nightmares.

2. Process and Labor Efficiency

Walk your production floor. Is there wasted movement? Are there bottlenecks? Could a jig or a template shave 10 minutes off assembly time? That 10 minutes of direct labor saved goes straight to your bottom line. Cross-train employees so they can flex during peak times instead of you needing to hire temporary help at a premium.

3. Product Redesign (Value Engineering)

This is the big one. Can you use a slightly different, more affordable wood for the table underside without affecting durability or look? Can you simplify the design to use fewer connectors? I worked with an electronics assembler who reduced their COGS by 15% simply by working with their engineer to specify a functionally identical but more common (and cheaper) capacitor. They didn't tell customers; the product performed the same. The entire saving fell to their gross profit.

A Real-World COGS Case Study: "Brewed Awakening" Coffee Roastery

Let's look at a real scenario I helped with. "Brewed Awakening" roasted and sold premium coffee. Their gross margin was stuck at 50%. They wanted to get to 55% to fund expansion.

The Problem: Their COGS seemed high. The green coffee beans were their biggest cost, and they just accepted market prices.

The Analysis: We broke down their COGS per 12-oz bag selling for $16:

- Green Coffee Beans: $5.50

- Packaging (bag, label, valve): $1.80

- Roasting Labor & Gas: $0.70

- Allocated Overhead (roaster depreciation, warehouse share): $0.50

Total COGS: $8.50

Gross Profit: $7.50 | Gross Margin: 46.9% (They were already miscalculating slightly).

The Actions:

1. Supplier Strategy: Instead of buying small batches from a distributor, we connected them directly with a cooperative of farmers for their core blend. This cut the bean cost to $4.75 per bag, but required a larger upfront commitment.

2. Packaging: They switched from a custom-printed bag for every blend to a high-quality standard bag with a sticker label for the blend name. Saved $0.40 per bag.

3. Process: They optimized their roasting schedule to do larger, less frequent batches, reducing gas waste. Saved $0.10 per bag.

The New COGS: $4.75 + $1.40 + $0.60 + $0.50 = $7.25

New Gross Profit: $8.75 | New Gross Margin: 54.7%

They hit their target. The key was attacking COGS from multiple angles, not just hoping bean prices would fall.

Your Top COGS Questions, Answered

Mastering COGS isn't about being an accounting whiz. It's about understanding the economic engine of your product. Stop looking at it as just a line on your income statement. Start treating it as a set of variables you can control. Track it accurately, analyze its components, and attack it strategically. That's how you turn cost control into profit maximization.