Let's cut to the chase. If you're running a business and not tracking your gross margin, you're flying blind. You might see money coming in, but have no real idea if your core product or service is actually profitable. I've seen too many owners focus on top-line revenue, celebrating big sales, only to wonder later where all the money went. The culprit is often a weak or misunderstood gross margin.

What You'll Learn in This Guide

What Gross Margin Really Means (Beyond the Textbook)

Forget the dry accounting definition for a second. Think of your gross margin as the fuel efficiency of your business engine. Revenue is how much gas you put in the tank. Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) is how much gas the engine burns just to move the car. Gross profit is the gas left to run the air conditioning, the radio, and actually get you somewhere useful (that's your operating profit and net profit).

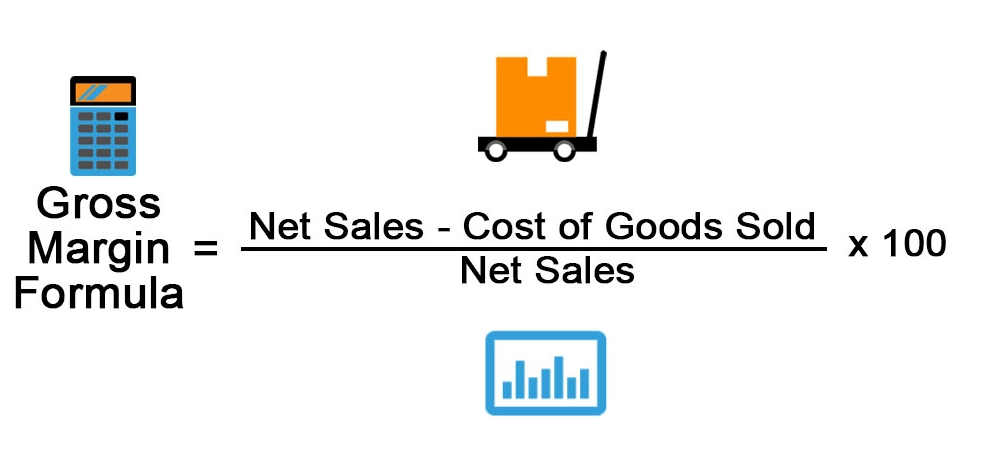

Formally, gross margin is the percentage of revenue left over after you pay for the direct costs of producing what you sell. It answers a fundamental question: For every dollar of sales, how much is left to cover my overhead and generate profit?

Here's the subtle point most miss: Gross margin measures your pricing power and production efficiency before your own operational bloat gets involved. A high gross margin means you either command good prices or manage direct costs well (or both). A low one means you're vulnerable; any increase in rent, software costs, or marketing spend hits you hard.

How to Calculate Gross Margin: The Step-by-Step Process

It's simple math, but the devil is in correctly identifying the numbers. Let's walk through it.

Step 1: Find Your Net Revenue

This is not just your total sales. It's total sales minus discounts, refunds, and allowances. If you sold $100,000 worth of goods but gave $5,000 in early-payment discounts and had $2,000 in returns, your net revenue is $93,000. Starting with gross sales is the first common error.

Step 2: Calculate Your True Cost of Goods Sold (COGS)

This is the critical part. COGS includes only the direct, variable costs tied to producing each unit you sell. For a physical product, that's:

- Raw materials

- Direct labor (wages for workers on the production line)

- Manufacturing supplies

- Freight-in costs

- Direct overhead for production (like factory utilities)

It explicitly excludes indirect costs like marketing, sales salaries, office rent, administrative salaries, and distribution costs. Those come later.

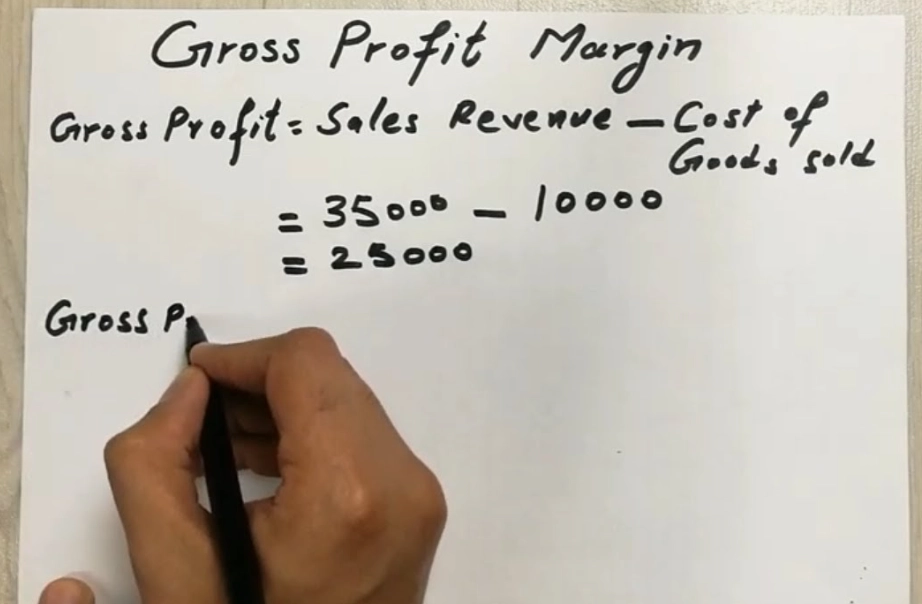

Case Study: The Curious Case of "Bean There" Coffee Roasters

Let's make this real. Say "Bean There" roasts and sells premium coffee.

In a Quarter:

- They sold $120,000 worth of coffee bags.

- They offered a "subscribe & save" discount totaling $8,000.

- Net Revenue: $120,000 - $8,000 = $112,000

Their COGS included:

- Green coffee beans: $40,000

- Packaging (bags, labels): $12,000

- Wages for the roaster: $18,000

- Electricity for the roastery: $3,000 (estimated portion for production)

- Total COGS: $40,000 + $12,000 + $18,000 + $3,000 = $73,000

Gross Profit: $112,000 - $73,000 = $39,000

Gross Margin %: ($39,000 / $112,000) x 100 = 34.8%

So, for every dollar of net sales, about 35 cents is left to pay for the shop rent, barista wages, marketing, and hopefully, some profit.

The Gross Margin Mistakes Almost Everyone Makes

I've consulted for small businesses for years, and the same errors pop up.

Mistake 1: Confusing Gross Margin with Markup. Markup is the percentage you add to your cost to set the price. If a product costs you $50 and you sell it for $100, that's a 100% markup. But the gross margin is ($100 - $50) / $100 = 50%. They are not the same. Using them interchangeably will wreck your pricing strategy.

Mistake 2: Inflating Revenue. Using gross sales instead of net sales, as mentioned, makes your margin look better than it is. It's a dangerous illusion.

Mistake 3: Under-calculating COGS. The big one. Business owners often forget to include all direct labor or a portion of direct utilities. That part-time helper who packages your products? Their wages are COGS. The electricity for your sewing machine? If it's directly used in production, a portion belongs in COGS. Leaving these out artificially inflates your margin, making you think you have more breathing room than you do.

Mistake 4: Comparing to the Wrong Benchmark. A 30% gross margin might be terrible for a software company but fantastic for a grocery store. You need industry context.

What Your Gross Margin Number is Telling You

So you've crunched the numbers. What now? Your gross margin is a diagnostic tool.

If it's trending down over time: Your costs are rising faster than your prices. Are supplier costs up? Are you becoming less efficient in production? Are you discounting too heavily?

If it's lower than your industry average: (Check reports from sources like the IBISWorld or NYU Stern's margin data). You're at a competitive disadvantage. You may have a cost structure problem or lack pricing power.

If it's high and stable: This is the sweet spot. It means you have a strong value proposition (customers will pay your price) and efficient operations. You have room to invest in growth or withstand market shocks.

Here’s a rough guide to typical gross margin ranges across different sectors. Use it as a starting point, not a definitive rule.

| Industry | Typical Gross Margin Range | Why It Varies |

|---|---|---|

| Software/SaaS | 70% - 90% | Very low COGS after initial development; costs are mostly in R&D & marketing. |

| Consulting/Professional Services | 50% - 70% | COGS is primarily direct labor. High margin relies on billing rates significantly higher than salary costs. |

| Manufacturing (Consumer Goods) | 30% - 50% | Includes costs of materials, factory labor, and equipment. Highly competitive, volume-sensitive. |

| Retail (Clothing) | 40% - 60% | COGS is the wholesale price paid for inventory. Markup is key, but competition and discounting pressure margins. |

| Restaurants | 25% - 35% | High and volatile food costs (COGS), combined with fixed labor. A tough margin business. |

| Grocery Stores | 20% - 30% | Extremely high volume, very low margin per item. Efficiency and turnover are everything. |

Practical Ways to Improve Your Gross Margin

You have two levers: increase revenue per sale or decrease COGS per unit. Often, it's a mix.

On the Revenue Side:

- Re-evaluate Pricing: Can you increase prices by 5% without losing too many customers? Even a small increase flows straight to gross profit. Test it.

- Bundle Products: Sell a higher-margin item with a lower-margin one at a combined price that improves the overall transaction margin.

- Reduce Discounting: Analyze your discount strategies. Are they driving volume that actually improves total profit, or just eroding your margin? Maybe tighten the terms.

On the COGS Side:

- Negotiate with Suppliers: Can you get better terms for buying in larger volumes? Even a 2% discount on materials adds up.

- Improve Operational Efficiency: Reduce waste in production. Can your process use less material? Is there less rework? This is pure margin gain.

- Re-source Materials: Explore alternative suppliers or materials that meet quality standards at a lower cost.

- Audit Your COGS Allocation: Make sure you're not accidentally including overhead. But also make sure you're not excluding true direct costs. Accuracy itself can reveal opportunities.

The goal isn't necessarily to have the highest margin, but to have a sustainable and understood margin that supports your business model.

Your Gross Margin Questions, Answered

Mastering your gross margin calculation isn't about passing an accounting test. It's about gaining a clear, honest view of your business's core profitability. Start by calculating it for last quarter. Then track it monthly. You'll begin to see the story it tells about pricing, costs, and the fundamental health of what you sell. That knowledge is power—the power to make smarter decisions and build a business that lasts.