Let's cut to the chase. A subsidy is financial aid given by a government or public body to support an industry, business, or group of people, making something cheaper to produce or buy than it would be in a free market. Think of it as a targeted financial nudge. The government decides something is important—like growing food, making clean energy, or educating people—and uses public money to lower its cost.

But here's the part most basic definitions miss: a subsidy is always a transfer. Money doesn't appear from thin air. It comes from taxpayers (you and me) or is borrowed, and is given to a specific recipient. This creates winners and losers, intended and unintended consequences. It's a powerful tool, but one with significant side effects that don't always make the headline.

What You'll Learn

The Simple Mechanics: How a Subsidy Actually Works

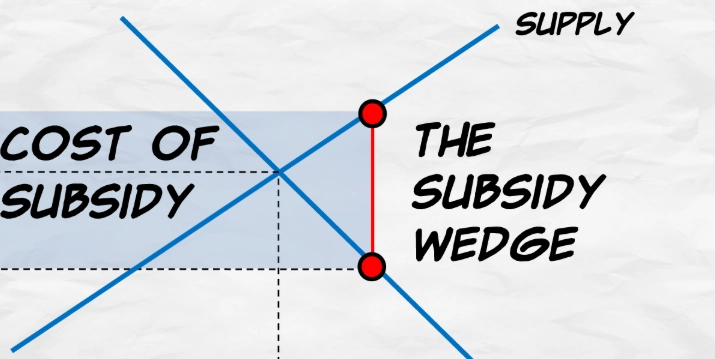

Imagine you sell solar panels. They cost you $500 to make and you sell them for $600. A customer thinks $600 is too high. The government wants more solar power, so they offer you a $150 subsidy per panel. Now you have choices.

You could keep your price at $600 and pocket the extra $150 as pure profit. That's tempting, but it doesn't achieve the government's goal of making solar more affordable.

Or, you could lower your price to $450. For you, the math is the same: $450 (customer price) + $150 (subsidy) = $600 total revenue. But for the customer, the panel is now much cheaper. Demand will likely rise. This is the classic supply-side subsidy flow.

On the consumer side, think of an electric vehicle (EV) tax credit. The car costs $40,000. The government offers a $7,500 tax credit directly to you, the buyer. Your effective cost drops to $32,500. That's a demand-side subsidy, designed to make you more likely to buy the EV.

The mechanism is simple. The politics and economics around it are anything but.

The Four Main Types of Subsidies (With Real Examples)

Subsidies come in different wrappers. Knowing which is which helps you understand their impact and, if you're a business, how you might access them.

| Type | How It Works | Real-World Example | Who It Reaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Cash Grants | Straightforward payment from government to recipient. | A small business grant from a city's economic development fund to open a store in a struggling neighborhood. | Very direct, but competitive and paperwork-heavy. |

| Tax Breaks & Credits | Reduces the amount of tax owed. A credit is more valuable than a deduction. | The R&D Tax Credit allows companies to deduct a percentage of research expenses from their tax bill. | Benefits profitable companies that owe taxes. Useless for startups with no profit yet. |

| Low-Interest Loans & Guarantees | Government provides loans below market rate, or guarantees a bank loan (reducing risk for the lender). | The U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) 7(a) loan guarantee program. | Helps businesses that are "bankable" but might not get ideal terms privately. |

| Price Supports & Purchases | Government guarantees a minimum price for a good, or buys surplus to keep prices stable. | Historically, U.S. farm policy bought excess cheese, milk, etc., to support dairy farmers' income. | Directly supports producers in volatile commodity markets, but can lead to overproduction. |

There's also the sneaky one: in-kind subsidies. This isn't cash, but something valuable provided for free or cheap. A university letting a biotech startup use its lab equipment for a nominal fee is an in-kind subsidy. Government-provided workforce training programs are another.

Why Governments Love Them: The Intended Benefits

When subsidies work as planned, they can be brilliant policy tools.

Supporting Strategic Industries. This is the big one. Every nation wants food security. Relying entirely on imports is risky. So, countries from the U.S. to Japan to India subsidize farmers to ensure a stable domestic food supply, even if it's not the globally cheapest. The same logic applies to renewable energy, semiconductor manufacturing, or aerospace.

Correcting Market Failures. Sometimes the free market underinvests in things that benefit society broadly. A company might not invest enough in clean tech because the upfront cost is high and the public benefit (clean air) isn't something they can sell. A subsidy bridges that gap, aligning private incentive with public good.

Social Welfare and Equity. Subsidies on essentials like heating fuel for low-income households, school lunch programs, or public transportation fares aim to make life more affordable. The goal here isn't economic efficiency, but social stability and fairness.

Encouraging Innovation in Risky Areas. The early stages of tech like mRNA vaccines or carbon capture are high-risk. Government grants (like those from the U.S. National Institutes of Health or Department of Energy) can fund the foundational research that the private sector is too scared to touch alone.

I've seen this last one up close. A friend's company worked on grid-scale battery storage a decade ago, when venture capital thought it was science fiction. A Department of Energy grant kept the lights on long enough to prove the concept and attract serious private investment. Without that initial subsidy, they'd have folded in year two.

The Flip Side: The Downsides and Controversies

Now for the messy part. Subsidies are not magic. They distort markets, and those distortions have costs that often get ignored in the political cheerleading.

The biggest hidden cost? Inefficiency and Dependency. A business that grows reliant on a subsidy has little incentive to become truly efficient. I've consulted for manufacturing firms that stayed in high-cost locations only because of local tax abatements. The moment those abatements were set to expire, they threatened to leave. They never built a genuinely competitive operation.

Trade Wars and Global Distortions. When Country A heavily subsidizes its steel industry, it can flood the global market with cheap steel, undercutting producers in Countries B, C, and D. This leads to job losses abroad, accusations of dumping, and retaliatory tariffs. The global steel and aluminum markets are a textbook case of this subsidy-driven tension.

Misallocation of Resources. Money spent on propping up a fading industry (like coal) is money not spent on building the industries of the future. Politicians often subsidize the past to protect current jobs, potentially hindering long-term economic adaptation.

The "Who Pays?" Problem. This is critical. A subsidy for electric cars is funded by all taxpayers, but initially only benefits those wealthy enough to buy a new EV. A subsidy for corn ethanol might raise food prices globally, hurting poor consumers worldwide to support farmers in one country. The benefits are concentrated and visible; the costs are diffuse and hidden.

And let's not forget administrative overhead and fraud. Designing a subsidy program that reaches the right people without being gamed is incredibly hard. The U.S. Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) during COVID-19 was a necessary speed-over-perfection measure, but it was rife with issues, from funds going to ineligible businesses to outright fraud.

Subsidies in Action: Two Major Case Studies

1. Agricultural Subsidies: The Forever Program

The U.S. Farm Bill, renewed every five years, is a subsidy behemoth. It started during the Great Depression to save family farms. Today, its effects are deeply debated.

How it works: A mix of direct payments, crop insurance subsidies, and price supports. The government heavily subsidizes premiums for crop insurance, guaranteeing farmers a revenue floor.

The Argument For: Stabilizes a vital, weather-dependent industry. Ensures a safe, abundant, and cheap domestic food supply. Preserves rural livelihoods.

The Argument Against: Critics point out that the majority of payments go to the largest, wealthiest farm operations, not struggling family farms. It encourages mono-cropping (like endless corn and soybeans) linked to environmental issues. It can distort global trade and make it harder for unsubsidized farmers in developing countries to compete.

It's a classic example of a subsidy that's incredibly hard to remove because a powerful constituency (farmers, agribusiness) depends on it.

2. Electric Vehicle (EV) Tax Credits

Countries from the U.S. to Germany to China offer thousands in subsidies for EV purchases.

How it works: A point-of-sale rebate or tax credit to the buyer. Some programs also fund charging infrastructure.

The Argument For: Accelerates adoption of cleaner technology, reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Helps domestic automakers compete in a new technological race, especially against heavily subsidized Chinese EV makers. Creates jobs in battery and EV manufacturing.

The Argument Against: Early on, it was a subsidy for the affluent. It can create a "cliff effect"—demand surges before a subsidy phases out, then crashes. There's also the question of picking winners: are battery EVs the only path, or are we subsidizing them over hydrogen or other potential solutions?

The recent U.S. Inflation Reduction Act tied its EV tax credit to North American assembly and battery sourcing. This shows a subsidy evolving from a pure environmental tool to one also serving explicit industrial and geopolitical strategy.

How to Find and Apply for Subsidies (A Practical View)

If you're a business owner or researcher, navigating the subsidy landscape is a skill. It's not about waiting for a check to arrive. It's proactive.

Start Local, Then Go National. Your city or state economic development agency often has grants for job creation, energy efficiency upgrades, or training. These are less competitive than federal ones. The U.S. federal portal is Grants.gov. In the EU, there's the Funding & Tenders Portal. These are your primary sources of truth.

Understand the "Why." Don't just look for money. Read the program's objectives. Is it to create jobs in a specific region? To develop a particular technology? To help a disadvantaged group? Your application must tell a story that aligns perfectly with that objective, not just your own need for cash.

The Application is a Marathon. It involves business plans, financial projections, technical descriptions, and impact statements. A common mistake is underestimating the time and expertise needed. Hiring a grant writer can be worth every penny if the potential award is large.

Compliance is Key. Getting the money is half the battle. You'll have reporting requirements—how you spent the funds, jobs created, progress metrics. Failing to comply can mean repaying the subsidy with penalties.

My advice after seeing dozens of applications? Treat a subsidy as a catalyst for a plan you already believe in, not the foundation of a plan you hope might work. The strongest applications are from businesses that would succeed anyway, but the subsidy will allow them to scale faster or take a smart risk.

Your Questions, Answered

How can a small business find and apply for relevant subsidies?

Start locally. Your city or regional economic development office is the best first contact, as they run programs with less competition than national ones. Prepare a solid business plan first; grant officers need to see viability beyond the subsidy. Many applications fail because they ask for money to fix a failing model, not to accelerate a good one.

Are subsidies considered taxable income for a business?

It depends entirely on the jurisdiction and the subsidy's purpose. Direct cash grants for capital expenditures are often taxable. Grants for specific research or development might be non-taxable under certain conditions. Never assume. The first line of your due diligence should be consulting a tax professional or the granting agency's tax guidance documents to avoid a nasty surprise at year-end.

What's the biggest mistake companies make when relying on subsidies?

Building them into their long-term financial model as a permanent fixture. Treat a subsidy like a strong tailwind, not the engine. I've seen startups collapse when a 2-year grant ended because they hadn't reached true cost efficiency. Your business model must be sustainable without the subsidy; the subsidy should just help you get there faster or undertake riskier innovation.